Fred and Loathing on The Internet

Welcome to the public web log of Fred Lambuth

Popular Tracks from 2024-03-19

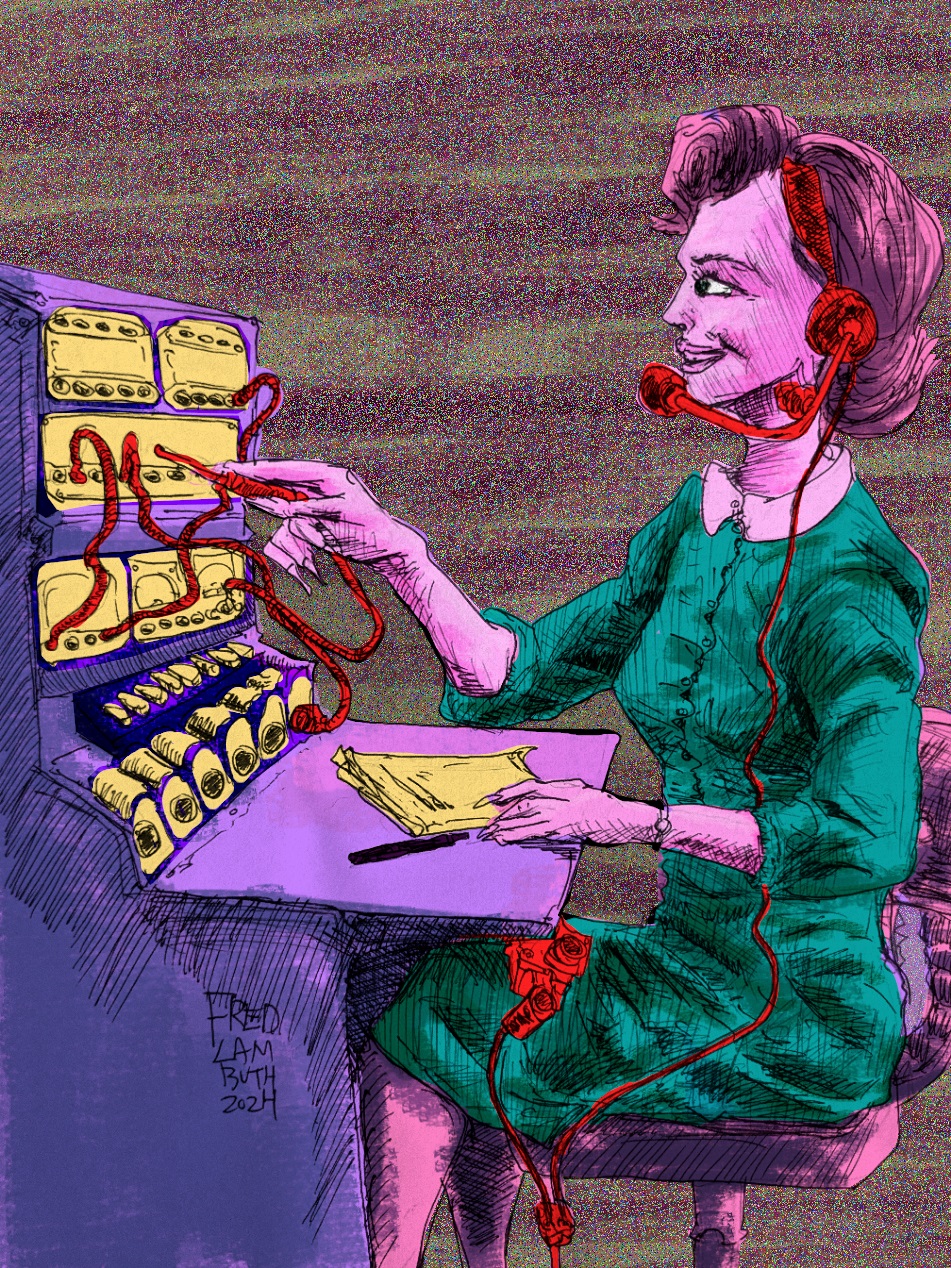

Dial P For Phreak

2024-Mar-19

Twice the normal content on this blog post. Two books reviewed! Well, maybe not two complete critiques of two books, but at least one with mentions of another. Both deal with the theme of ‘hacking’. Exploding the Phone by Phil Lapsley and This is How They Tell Me The World Ends by Nicole Pelroth. The former deals with a generation of technology, the telephone, that predates the official term ‘hacking’. The latter is an up to the minute (published in early 2021) look at computer hacking at the global level. Both are excellent and each play to a different sensibility I have for books. Hackers being outlaws. Misfits. Outsiders to official systems that hack away the unnecessary to get to their goals, no matter what is being ‘hacked’ away, like security. The book that had me more compelled to keep turning the pages was the more technically intricate Phone book by Phil Lapsley. Had I read them when I was younger, I might have gone the other way.

Both books include a cast of beautifully rendered misfit souls or straight laced agents of order. Pelroth chooses to give a less technologically heavy approach, instead informing on the geopolitical repercussions of these misfit hackers around the world. These hackers cause trouble for the tech giants by finding flaws in their products. They either inform them, use the flaw, or sell them to whoever might want to know about those flaws. Before they are generally known, these are zero day exploits. Unknown unknown flaws. Well, unknown to most.

Very lightly does she touch upon what are the actual technologies involved in these hacking exploits she reports on. We find out Apple was snooped around, or Kiev’s power grid was disconnected, or that the multi-national effort Stuxnet moved around systems in a closed network in Iran’s nuclear facilities. I was looking for a deeper bite into the technological vectors that are being leveraged by hackers. Pelroth keeps things at a nominal level of who was attacked but the ‘how’ question is left unaddressed. I can imagine making a compelling read that blends Pelroth’s quick journalistic sensibilities and a close look into the grit of the tech involved in finding zero day exploits in software is difficult to pull off.

Exploding the Phone has an older and more documented network being hacked, the coast to coast American telephone network, which Phil Lapsely succinctly explains in 330ish pages. Lapsely efficiently weaves between the tales of the phone phreaks origins and misadventures and the physical engineering of the whole damn network. Phreaking is the somewhat self-coined term of the early vandals of the analog telephone network that blanketed most developed nations in the mid-20th century. The ‘phone system’ was a network of connected analog circuits with switches in between with some type of control mechanism to switch the path of the circuits. Switching was done to connect callers hundreds of miles apart through possibly several somewhat independent phone systems.

Every phone call between short or long distances ultimately involved creating a path for the audio of your local phone line to your caller. This could be in the same ‘switch’ in your neighborhood, or the orchestration of paths being made by many coordinating switching stations finding a path for your call. Early manual switching with phone operators could take minutes due to human hands looking in binders of codes and maps showing how two distant phone networks could make a mutual circuit path.

Once that call was connected, there was an ongoing path for your audio signals vibrating a phone handset, shaking the lines until it shook the destination phone set. Not quite two soup cans connected by string, but ultimately following that same connecting logic. The US phone system was a very big network of audio lines with switching stations at localities that would have hierarchical relationships with routing stations above them. Each network was a big connecting machine hooked up to AT&T’s big long distance network.

The phreaks come into the story by probing around the phone network with their rented phone sets. In the USA, the one and only telephone company AT&T, did not allow any connection to their network with equipment that was not owned by them, to include phone sets used by every customer. AT&T the corporation that held a national monopoly on long distance phone lines is a character itself in the story. Other nations themselves had one big phone company. The USA never bothered to nationalize the company, like most other nations. Instead AT&T had an uneasy relationship with the national government as the only legal provider of long distance phone service until its eventual mutilation into smaller phone companies in the late 80s. (I remember a somewhat disingenuous plea from a relative thinking Taco Bell was the baby Bells from the AT&T breakup servicing the south Texas area.)

These phreaks used their phones to discern just what the noises in between the sound of people talking meant. The sound of the phone hanging up. The dial tone. The change in pitch when you dial with a touch tone versus the throbbing of a rotary phone. Turns out quite a bit of these early phone phreaks that came on to the scene without learning from outside sources were blind kids. Boys I should say. I do not recall any prominent stories in the book about any women phreaks. Women do participate in the story when operators were common in the phone connection process. The phreak boys would get their girlfriends, sisters, or any woman on hand, to be their voice when talking to inner network operators who assist local network operators. A woman's voice gets less flak from the women operating the inner workings of the phone network that should not be available to the normal telephone caller.

The blind kids have a natural talent for finding peculiarities in the phone network because the phone network in its earliest phases were controlled by frequencies low enough for the human ear to catch most of them. These earliest phreaks found through their own probing some holes in the normal operation of phone calls. With some careful study of patterns in how the phone sounds from dialing, connecting between calls, or any minutia of tiny audio queues, these phreaks found ways to make free phone calls.

The stakes are much lower in the tales of the phone phreaks in the 50-80s than the national army hackers in Nicole Pelroth’s books. The phreaks were kids who just wanted to have fun, maybe make a few bucks at the expense of using a national monopoly’s resources. This era also allowed for a much more secretive world of hackers. Either phreaks bumped into each other using the same exploits on the phone network, or they sought each other out in the real world in such archaic manners like printed ads in the newspaper.

By the late 60s the phreaks broke out of this secret network of early adopters and brought in outsiders via yippie publications that encouraged the illegal use of the US phone network. With this scale of phreaks messing around, finding flaws in their network, the phone company stopped tolerating these phreaks as just ‘boys will be boys’. This was now a mass effort to defraud a national institution and possibly a case of perpetrators hoping to damage the country through the phone system.

The idea of a phone system that could allow a malicious actor to convince a national level actor to launch a nuclear missile seems implausible to me now. Exploding the Phone does a convincing job laying out just how the phone network was the backbone of information in a pre-Computer age, such as launch codes. This phone network had security measures that were supposed to insulate the average phone user from the military network. Ultimately these secure phone networks were vulnerable to the same audio signal tricks that phreaks deal in. Any phone network that was using audio tones to transmit switching information could be exploited by somebody faking the sounds and transmitting them through their phone. I suppose the stakes for the kids messing with the phone could have gotten as dire as Nicole Pelroth’s hackers. The worst actual exploit I heard about was some kid possibly getting Dick Nixon on the phone by finding the number for the hotline to the Oval Office. A federal agent later possibly repeated the trick. I smile at the thought of Nixon’s jowls shaking up a storm as he curses out some kid or FBI Agent on the White House hotline.

The fun and games of punks messing around the phone network ends up with organized crime bringing in the chance for legal precedent to be made about how the law is supposed to treat the phone communication between two users of a company’s network. These mob interlopers into the phreak world get their comeuppance by getting sentenced for gambling, or racketeering or other conventional crimes that were perpetrated by illegal uses of the phone network. Most of the kids come out roughed up by the law or the phone company, but eventually come out as upstanding members of society that found good use for their technological curiosities.

I ought to mention Steve Wozniak, the brains of the founding duo of Apple Computers, was reportedly the salesman of the ‘blue box’ phreaking tool to hundreds, including celebrities. Wozniak himself writes the introduction to this book, offering the warmest words about his time as a phreak, along with how what he learned from those efforts were foundational to his ideas about what could be done with a computer. The tail end of the book mentions the bridge between computers and the homemade audio tone generating ‘blue boxes’. The early DIY computer scene of the 70s was a hotspot for phreaks. The first crude computers did a spiffy job of generating the tones needed to move around the increasingly digitized phone network. Those early computers really did not do much besides math operations outputted through beeps or tones.

Steve Jobs is mentioned, but only as a named friend that helped Wozniak handle the actual selling of the blue boxes. I’m sure Jobs liked the appeal of the misfits he saw doing it themselves with loose circuit boards to make their own computers. They sound like the people that were supposed to be thought of when hearing the tagline for Apple products in the , ‘Here’s to the crazy ones’ campaign for Apple in the . People who are crazy enough to click on the switches of a phone all day until they discover how long distance phone calls are made.

I certainly do not think that about Steve Jobs. A third piece of media to tack into this blog post: I had been listening to the four part series of Steve Jobs episodes from the Behind The Bastards podcast. Say whatever you want about the man, phone phreak or somebody that enjoys tinkering with stuff is not something I would say about Steve Jobs. Wozniak on the other hand sounds like a St. Francis of computers. Bless his soul.

I recommend both books. Exploding the Phone might not be for everybody though. Had I not a solid grounding in transmitting signals over phone lines I would have found a lot of the technical explanations to be pops and buzzers in my brain.

Add Comment