Fred and Loathing on The Internet

Welcome to the public web log of Fred Lambuth

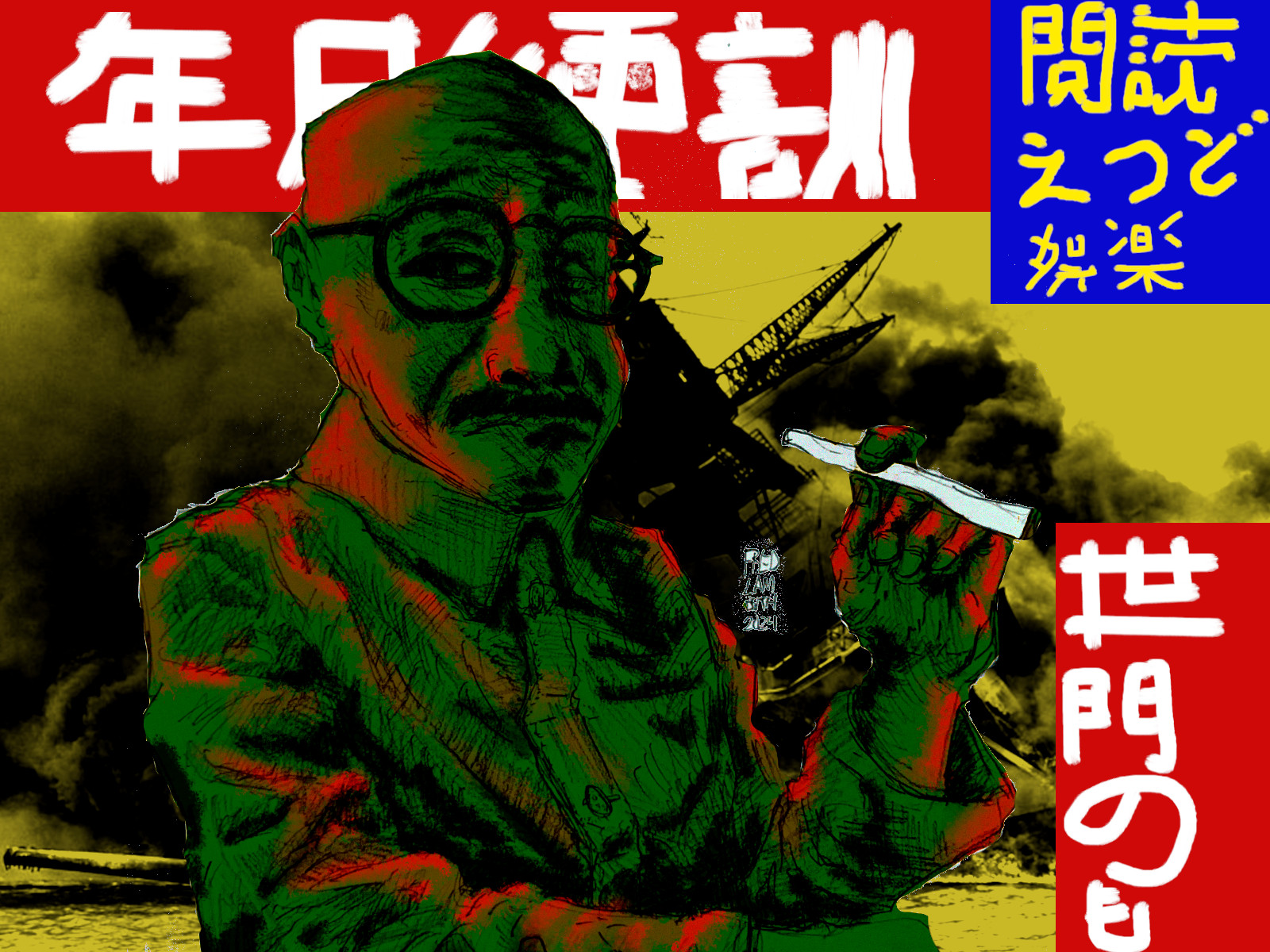

War Crimes Enough For Two Wars

2024-Nov-16

It’s not all chit-chat about comic books or old sitcoms here at the fredlambuth.com blog!

This time it will be my thoughts on all +1000 pages of Judgement in Tokyo by Gary J. Bass. A mammoth single volume, published in 2023, dealing with the convening of a court made to find ‘justice’ after the Pacific War ended with the Empire of Japan’s defeat. I read these heavy history books to cram the smartness found among the author’s words into myself. This book offers plenty to cram in. Plenty of studied exploration into the repercussions of Japan trying (and failing) to become a global imperial power. Oodles of thought provoking ideas that come up when applying the hard scrutiny of a courtroom on to the high minded ideals the victors of the war professed when cleaning up their victory abroad.

As has been mentioned on at least one blog post here (the one about the Shogun miniseries), my affinity for Japan is higher than for most countries. I probably mentioned back then that this cultural enthusiasm stops where most ‘Weebs’ would begin to be interested. WW2 is around where my interest hits a deadend. Sure, my curiosities as a political science student and a Navy vet have had me peer into what Japan is up to geopolitically. WW2 is that crossing point in Japanese history that changes from ‘samurais’ to ‘crucial factor to the Pacific realm of the USA’s global hegemony’. My interest in Japanese history after 1945 is purely academic. Even though I am kinda interested in how the manga/anime/kaiju film industry was created right after the war… Or the plight of the salaryman… Whatever, that’s for later blog posts.

The nation of Japan, I feel, offers a rebuttal to the idea that only white people AKA (the people who came out of Europe in the second half of the last millennium) benefited from modern imperialism. I hope this does not come off as cheers for the successful war efforts of Imperial Japan upon all its neighbors. Rather I hope it means I think it would be laughable for the victors of World War 2 to hold Japan accountable for wars of ‘aggression’. Japan was just playing the same game as the US, UK, France, and the Dutch. They knew it and that is why a full throated indictment of the Empire of Japan’s behavior could not be given by the war’s victors. Under the scrutiny of law, the authority behind the court (the war victors) prosecuting Japan were just as guilty.

Well, except for some particular crimes that proved hard to cement together in a court of law.

Such as the US’s particular grievance: the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. The treatment of prisoners of war. Or most gruesome, disasters such as The Rape of Nanking. National ‘crimes’ such as these were on the docket for the rapidly assembled panel of international judges. New judicial ideas in international law were muddled into the charges. Using new concepts about ‘war of aggression’, which sound an awful lot like what the nations of the victorious party did when they made their own expansions into Asia.

This book has shown me that the court was a lofty idea that quickly became a bad one once everything was put together. (It also showed me of the court's existence. I had heard of Nuremberg, but took for granted if there had been a counterpart for the Pacific War) When the zeal of victory and for the righteous pursuit of justice, to seal it all together in a nice package, had to bear the light of day in a courtroom.

What is ‘the court’? After the Emperor of Japan surrendered to the US in August of 1945, justice (or at least recriminations) were demanded by everybody. Especially the Americans. They were the ones that footed most of the bill for winning the war against Japan. The full roster of the aggrieved parties is: the USA, the USSR, the UK, France, Australia, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Canada, China, The Philippines, and India. Each country was allowed to send one ‘justice’ to Tokyo. By allowed, I mean a consensus was reached amongst the heads of state of the victors, and with tacit approval of General Douglas Macarthur. He assumed ‘Supreme Command’ in Japan’s capital after the Emperor surrendered. Although Macarther did want trials, he preferred speedy military tribunals on conventional stuff about treatment of POWs or the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. After plenty of soothing to Macarthur’s ego, he felt he was the one making the decision, and approved of putting together the Nuremberg of the Pacific. Nuremberg being the somewhat popular shorthand to refer to the trial put together by the allied victors of The War in Europe.

Personally I knew enough about Nuremberg to somewhat fill in the blanks to the story there. There are not too many deviations in the trial at Nuremberg story from the expected plan of ‘show how the Nazis were worse than your usual war aggressors’. The muddled collection of judgements issued by the court in Tokyo is likely a large reason why the court did not have as much historical impact as Nuremberg did. Perhaps it got buried even during its own time by more sensational stories in the news. By the time the judgment was rendered on the eve of 1949 the zeitgeist had more stories about nuclear bombs and rockets to space. Stories about the new age. Commiserating about prisoners dying of jungle rot intentionally or not might have been bland holdovers of a war wanting to be forgotten by the people who lived through it. Or too worried about the next war.

The book’s topic pulled me in because I am curious about the twilight period of the Asian countries that asserted their independence after WW2. Japan being a temporary Imperial landlord offers a lot of discussion about the motives for the victors of the Pacific war, before and after they did not have access to their colonial jewels. I do not mean to paint the Empire of Japan as liberators. What I want to do is paint them as the new racketeers in their hemisphere. New boss, same as the old boss. Moving in for the same reason the Europeans did, they want resources, they want it now, and they don’t care too much about the people living on the land that bears the resources.

That may sound like I am looking for new ways to vilify the US, or any of the members of the allied nations that won over the Empire of Japan. Their behavior in the years right after the war provides enough vindication about their villainous international policy. Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia each had to fight their way out of their old landlords assuming ownership from France, UK, and The Netherlands, respectively, after a quasi-joint effort to flush out the Japanese as landlords in all those nations. The US gave up the Phillipes right away, but just could not resist getting sucked into Vietnam's war for independence a few years after France gave up.

Had the book been just the story of the justices assembled to settle this judicial boondoggle, the book would probably be half in length. Just what is going on in the whole of Asia outside of the courtroom fills up the other half. It would be almost impossible to tell the courtroom story without the addition of international changes at the time. The story of the justice sent by Nationalist China shows a mirrored path as the political development of mainland China. He starts as a champion of Chang-Kai-Shek’s cause and ends his career as a respected elder of red Chinese judicial theory.

The star of the dissenting opinions is the justice dispatched by the newborn Indian nation. Radhabinod Pal found every single accused individual not guilty of all charges. The long and short of his opinion was that Japan was doing no wrong compared to what the nations it fought were doing. I don’t quite remember if he made any sort of agreement to the idea put forth by some of the testifying Japanese ministers that the war Japan fought was defensive. This Indian judge became a celebrity in Japan, especially among the non-apologetic rightwing of that country.

Much more could be said about how the Emperor was handled, or how the Soviet justice tried to sneak in unrelated Soviet history into the court record, or the war in China going to the commies before the trial’s end. It’s a big fat book. If you like that sort of stuff, this book does little to no wrong.

I’m off to my next big fat history book about a post-WW2 trial. This time about that Petain fellow in France.

Add Comment